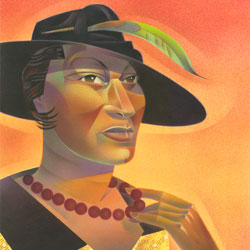

Photo: Melody Komyerov

With the publication in 2000 of his first illustrated children’s book, Henry Hikes to Fitchburg, D.B. Johnson has made a distinct mark in the world of children’s literature by introducing kids to the important ideas and work of the likes of Henry David Thoreau, George Orwell, M. C. Escher and René Magritte. In addition to the praise he has earned for his original picture-book stories, Johnson’s art has won numerous awards, including The Boston Globe/Horn Book Award for Best Picture Book, a New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book, and a Publishers Weekly Best Book award.

With more than twelve acclaimed print books to his credit, Johnson founded Moving Book Press in 2015 and launched a new career writing, illustrating, and animating picture e-books for kids.

Member: Society of Illustrators

A SHORT BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Sometimes the things that are best for your whole life happen when you’re very young.

I was three years old. My father moved our family into a house he built on a country road in New Hampshire. The house was unfinished inside, so we were able to see through the open framework from the living room all the way to the far bedroom.

That first winter we kids, all five of us, scrunched up around the fireplace at night before racing through the walls to our cold bedrooms.

There inside the covers at the foot of our beds, my mother had placed warm bricks wrapped in newspaper. In the morning we could see our breath and scratch the ice inside our windows.

It was a great polar adventure.

Summers meant family picnics and relatives from the city.

With them we flew kites and balsa airplanes in the field across the road. Every year Uncle Herb brought a box of paper left over from a year’s worth of jobs at his print shop. My Uncle Bud, an architect, drew wild characters he dreamed up on the spot. Once he gave us a Walter Foster drawing book. That year I used hundreds of sheets of paper copying his crazy faces and adding others from the drawing book. Every summer after that, I dived into that big box of paper and drew some more.

All that drawing got me a lot of friends. In school I became the “class artist,” but I didn’t take art very seriously. Mostly I roamed the woods and fields up and down our road. I loved the mile walk to the two room schoolhouse.

Each afternoon my mother, from the kitchen window, would glimpse me on our road two hills away. To her, that meant I’d be home in fifteen minutes. But one day after thirty minutes I still hadn’t arrived. When I finally walked in the door an hour late, she was very angry.

“What took you so long?” she demanded. I didn’t understand why she was so upset. “Mom!” I said, “I took the shortcut.” There it was. I lived in my own world of stonewalls, woodchuck holes and swamps.

In high school when I read Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden, I was surprised to hear the words of someone who loved the earth as much as I did. Later when I studied history and government in college, I read Thoreau’s words again. This time I understood, not just his ideas about nature but also his philosophy about how to live. If people weren’t working so hard to buy stuff, he said, they could spend more time doing what they love. That was an important idea.

I decided to spend my life doing art.

And so I have. More than thirty years ago, after we got married, my wife and I moved back to my small New Hampshire town. Here I worked for the local newspaper drawing cartoons for the letters page. Those cartoons were both funny and serious. Over the years my art became more illustration than cartoon, and it was printed in newspapers and magazines all over the United States.

From the beginning my wife and I made decisions about our family’s way of life that had nothing to do with money. Artists don’t get paid a lot, so we had to think about what kind of life we wanted and not what kinds of thing we would buy. I worked at home all day drawing pictures. My children could come into the studio any time to talk or to draw. In our home there was no television, but there were library books, and we read aloud to our kids until they were almost teenagers.